Five IMOCA were launched in the space of a month and a half in 2019. The Vendée Globe, which currently has 37 skippers pre-entered, will feature eight IMOCAs of the new generation that emerged from the Class Rule published on April 16 2019 by the International Monohull Open Class Association.

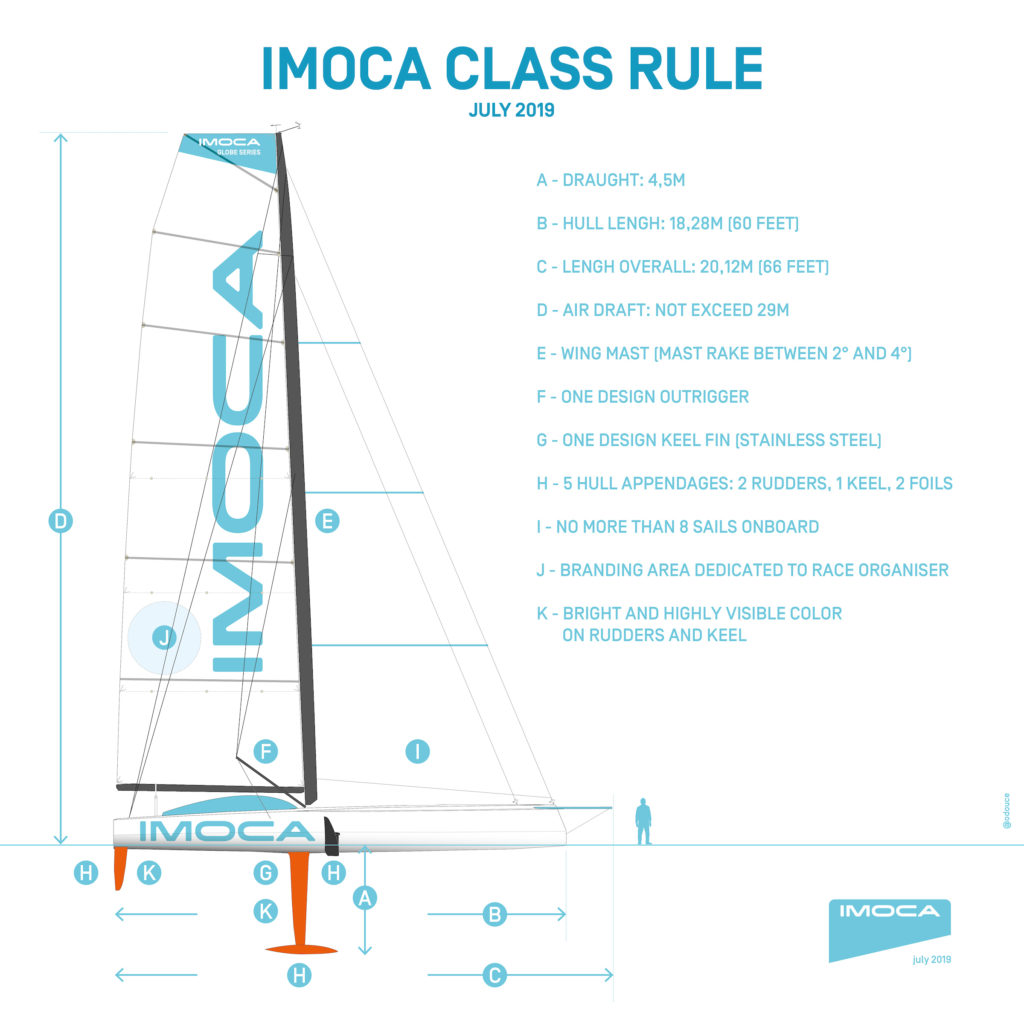

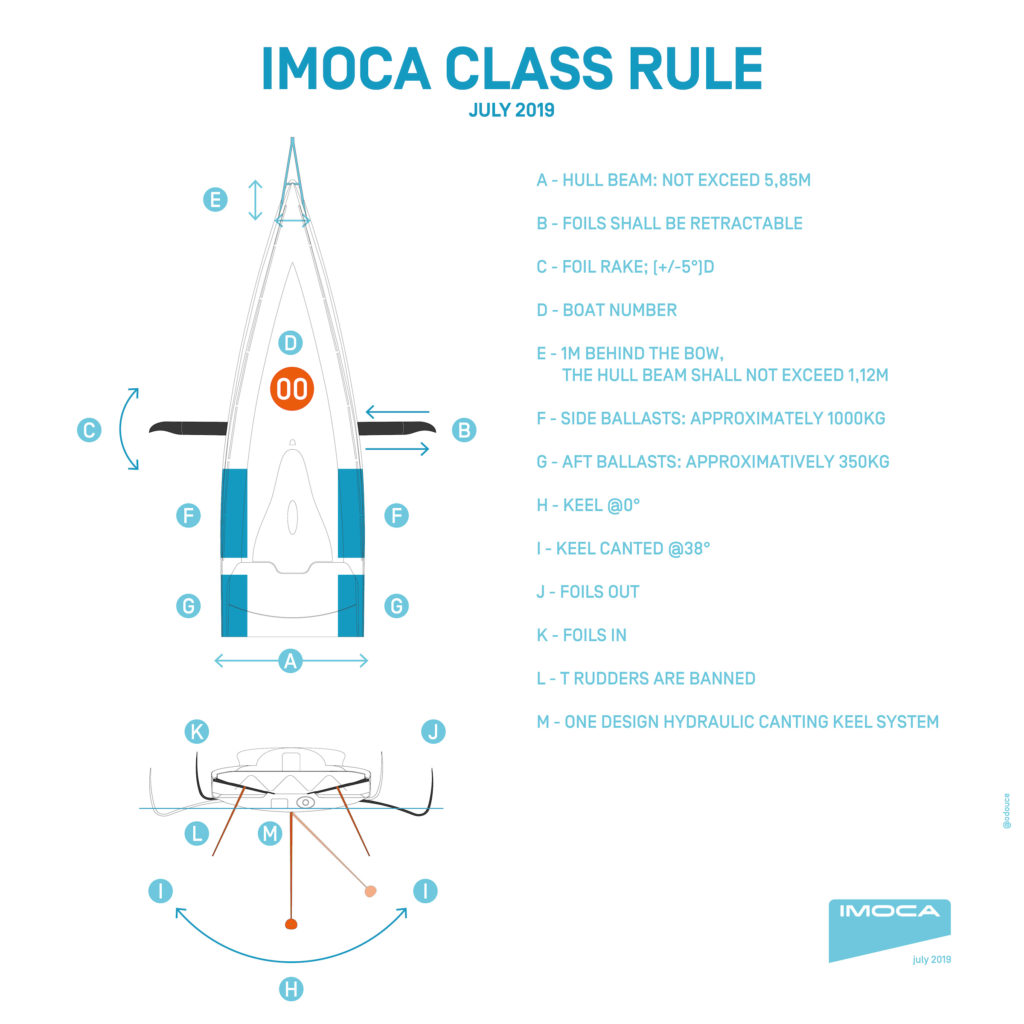

A Rule that aside from specifying LOA and hull (21.12 and 18.28 metres respectively) and draught (4.50 m), introduces a one-design mast and outriggers, keel fin and canting keel system.

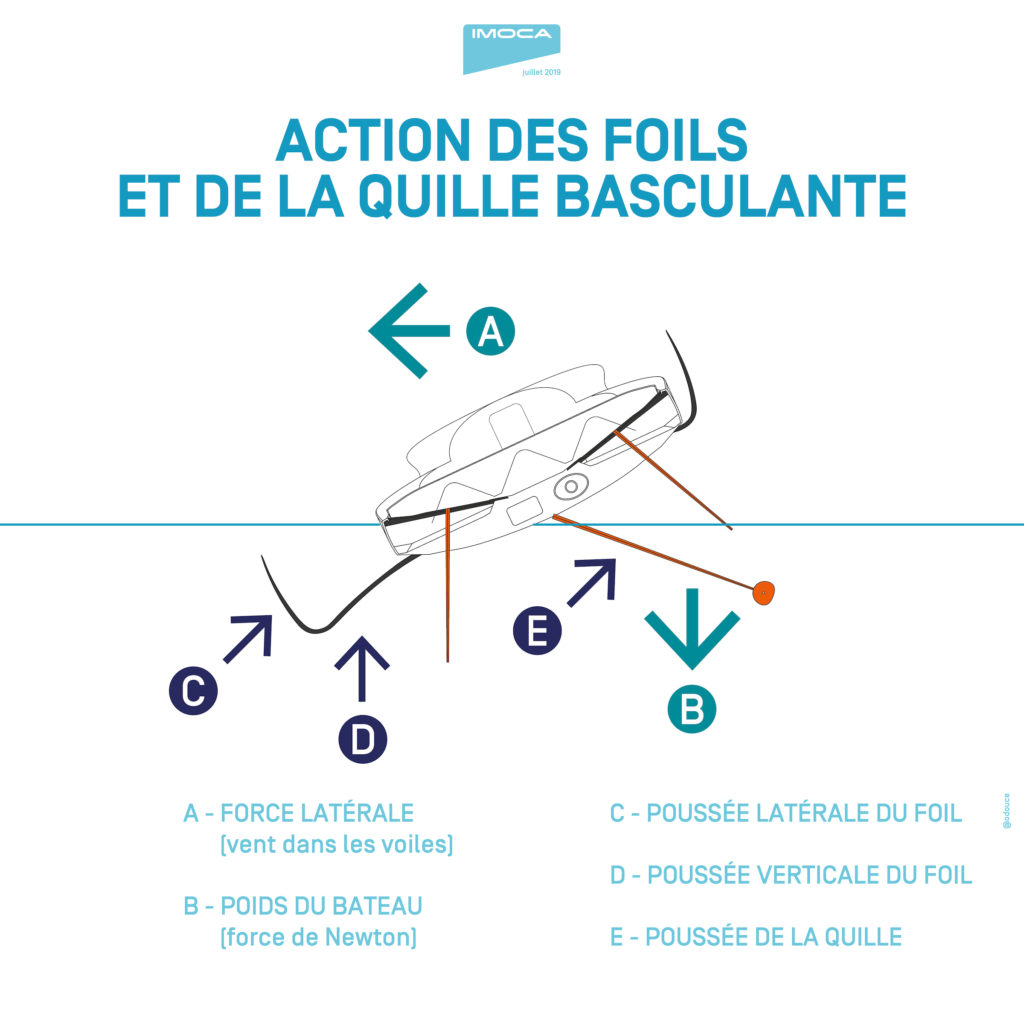

Most importantly of all, however, it ushers in a second degree of freedom for the retractable foils which can now not only extend from and retract into the hull but also rotate 5 degrees on their axes.

The Vendée Globe apart, the Ocean Race 2021-2022 is also on the calendar and will see the IMOCA racing alongside Volvo 65s. All in all, a whole series of factors that make the 18m open an extremely dynamic class from a design perspective.

This is why we brought together the designers of the IMOCAs launched in 2019 for a Q&A session: Vincent Lauriot Prévost of the VPLP studio which launched Hugo Boss and DMG Mori, Guillaume Verdier who launched Apivia (winner of the Transat Jacques Vabre) and Advens for Cybersecurity, and, of course, Juan Kuojoumdjian who penned Arkea Paprec and is currently involved in the build of Corum d’Epargne which hits the water in 2020. This is what they told us.

TYD: How do you define the “new generation”?

Vincent Lauriot Prévost. Very simply put the new generation of IMOCAs is made up of boats designed around their foils which are not an optional but central to the design.

Guillaume Verdier. The new generation doesn’t really mean much. Apart from the fact that these boats were created specifically for the 2020 Globe. Some of the old boats, like PRB (a 2009 VPLP-Verdier design which finished second in the last Transat Jacques Vabre, ed.’s note), have been upgraded and are sailing very well.

Juan Kuojoumdjian. New generation because they were designed according to the Class Rule published after the 2017 Vendé Globe which authorises a second degree of freedom for the foils. Usually, in addition to being able to extend and retract, you can choose another axis of freedom, in most cases, a vertical one to rake the foil forward or backward.

TYD: What is the difference between your two designs?

V.L.P. Rather than designing a hull for maximum power, we focused on obtaining it through the foils and developed the hull around minimum resistance criteria. Unlike their 2016 counterparts, the 2020 boats have a narrower hull, reduced waterline beam, and rounded edges which lift aft for a smaller wetted surface. DMG Mori came out of the same mould as Charal (launched in 2018, ed.’s note) and Hugo Boss’s hull philosophy is similar, but improved in terms of resistance thanks to further research. G.V. Both have benefited from 18 more months of research than usual because in 2017, we were chosen to develop the Super 60 for the Volvo Ocean Race. These boats are derived from that research (In May 2017, then-Volvo Ocean Race CEO Mark Turner launched the design of a 60’ One Design, the Super 60, for the 2019 edition but the project was later abandoned, ed.’s note).

J.K. There is a confidential agreement on the specifications… In common there is the hull mould, to reduce costs, and, of course, the one-design mast and keel. They have two different deck and cockpit designs, and different foil approaches.

TYD: Which element characterises the designs?

V.L.P. Hugo Boss’s deck is unprecedented. The forward profile is designed to reduce the surface area exposed to the wind, wave circulation and spray on the deck, which is flat. This is facilitated by the absence of a deckhouse of which DMG Mori has a traditional example. This allowed us to lower the overall centre of gravity and create a genuinely aerodynamic plane between the boom and deck. There is also no real aft cockpit and the working area is covered and sheltered.

G.V. There are a lot of them. The dimensions of the foils, the aerodynamic shape of the boats, the deckhouse as protection for the crew, the hull sections which are more or less full forward or round, and the sail plan.

J.K. The choice of the type of foil and the cockpit-coachroof. These are two very obvious elements because you can see the volumes and how the skipper wants to manage the boat, manoeuvre and check the sails. As you can already see, the deckhouse of Arkea Paprec has a series of windows towards the bow, when Corum l’Épargne decided to go without.

TYD: Did you develop the foils in-house in your studio and did you use aeronautics-derived software to do so?

V.L.P. The foils were designed entirely in-house. We have a team of engineers and architects, software which is mostly also developed in-house, computers and simulation systems to design the foils, keels and rudders for our projects.

G.V. We do everything in-house. We develop our own software and also use the simulator and instruments developed by Emirates Team New Zealand (Verdier is naval architect to the America’s Cup defender, ed.’s note).

J.K. Back in 2004 – since our first Volvo campaign (ABN Amro) – we decided to have our own high-performance computing cluster and run the CFD simulations in-house. This is what we call JYDcfd. For structural calculations, we combine our own resources with external consultants, while the systems are designed by each team.

TYD: What is the difference between the foils on the two designs?

V.L.P. Hugo Boss and DMG Mori’s foils are different but in both cases, the decision was to make the boat “flying” by giving them a deep draught which creates significant lift. The circular shape of Hugo Boss’s foils mean they can retract fully into the hull in light winds. Something that is not possible with other shapes.

G.V. The differences are clear when you look at the boats from the bow, in their extension and the chord, in the draught and the surfaces. Also the way they can be retracted in light winds.

J.K. It might be easier to comment on the fleet’s different approaches. This is very much depending on the strategy for the Vendée-Globe. There are two types of foils, the curved-circular ones optimised for downwind VMG and the more all-around ones, with a vertical tip on a more horizontal shaft. The skipper plays an important role in this decision, depending on his vision on how to sail these foilers.

TYD: Did you develop a safety system to tackle the risk of the foils striking floating objects?

V.L.P. No.

G.V. I would like to but it is beyond my abilities! We did have a thermal imaging camera on the mast head aboard Safran (the first foiling IMOCA penned by VPLP and Verdier in 2015, ed.’s note). That is a huge risk!

J.K. The designers of Juan Yacht Design are not directly involved in this one part. In our case, the decision is taken by each team to find the right balance.

TYD: What do you think the next evolution of the IMOCA will be?

V.L.P. The next IMOCAs should, if the class rule permits it, have lift planes under the rudders (T-foils, ed.’s note) to help with control when foiling. The crew and working areas will be more protected than ever and the manoeuvres on deck increasingly infrequent.

G.V. We really miss the T- rudders. Right now it is like trying to pilot a plane without any tail assembly to stabilise it in flight. It is a real pity. We would be six knots faster and it would be less dangerous.

J.K. Two elements will be fundamental. First, T-rudders with flaps for much better control in flying mode. Then, secondly, to authorise more freedom in foil control, even if the systems will be more expensive, they will give teams an efficient way to find the right balance without changing foils, which is far more expensive.