“It all began in 2009 in San Diego, California, with the wingsail for the Oracle trimaran for the 2010 America’s Cup” says Marc Van Peteghem of the OceanWings’ backstory.

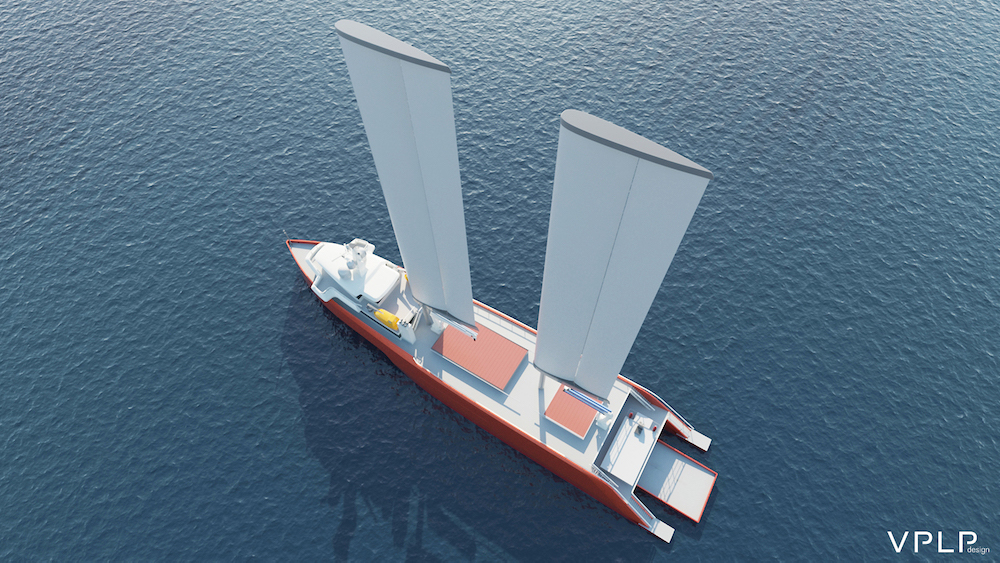

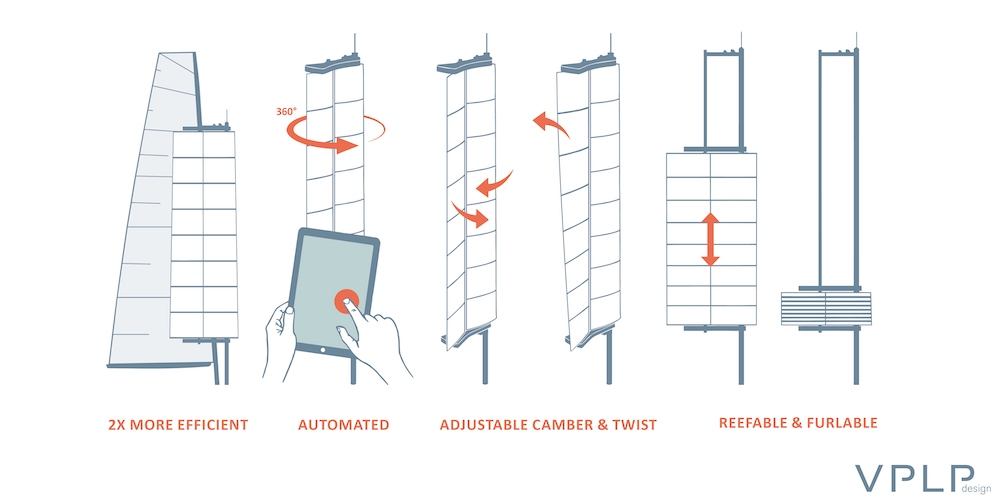

He heads the French studio VPLP with Vincent Lauriot Prévost that developed the latter radically innovative wind propulsion system which manages to retain the aerodynamic characteristics of a rigid wingsail but can also have the amount of sail surface exposed to the wind reduced because it is both furlable and reefable.

It is also automated and can be produced on an industrial scale. Most impressively of all, it is now moving from its experimental stage to concrete application.

“Vincent and I asked ourselves how that type of wing could be used for maritime transport. Whatever it was and technical problems aside, it needed to deliver economic results, a return on investment, and to pay for itself in terms of fuel savings in an economically reasonable timescale. Only then would it be useful,” says the designer.

VPLP developed its idea on paper for four long years and then with the financial backing of France’s Energy and Energy Management Agency, ADEME, it finally got to build an OceanWings working prototype in 2013. The latter comprises two wingsails which together create a system with a 21 square metre sail surface.

They can be manoeuvred too to optimise their angle of incidence to the vessel’s point of sail and can also be reefed. They are self-supporting and completely automated.

More importantly still, they are almost twice as efficient as a traditional rig. The OceanWings prototype has been fitted to an 8-metre trimaran, itself highly innovative. In fact, it is built from eco-composites made from linen fibre and recycled thermoplastic resins. On August 28 2013, the first sea trials began while R&D continued.

The big turning point came in December 2017.

“Since then we have found an industrial partner, CNIM, a large French group that works in environmental, energy and high tech sectors. So we have transitioned from the final design phase to actually using OceanWings on big catamarans like our Komorebi 200 and on Evergreen Marine Corporation vessels,” continues Van Peteghem.

“The shipping world – container ships, oil tankers, freighters and passenger vessels – is the very reason by we developed OceanWings.

The reason is simple. Almost 80 per cent of world trade is by sea and International Maritime Organization projections suggest that will rise to 90 per cent by 2050.

While pollution and greenhouse gases produced by maritime transportation accounts for just three per cent of the overall world figure right now, it is estimated that without intervention that will rise to 17 per cent by 2050.

This is why the IMO has set itself the goal of halving emissions by 2050. To do that the ships of the future will have to green.”

He adds: “We are working on a design for a 120-130-metre mercantile vessel that will be fitted with an OceanWings systems with six elements of 250 square metres apiece. It will save 25% on fuel on a six-knot Atlantic crossing”.

So it will be a sailing mercantile vessel?

“It’s a mixed system with OceanWings combined with a conventional auxiliary engine. It would be better if it was thermo-electric though. In terms of performance we worked with meteorological experts on weather data from the last 10-15 years.

As an initial solution, we set a series of starting data for the ship and calculated its performance on the basis of historic wind data.

As a second solution, we considered routage proper, a weather research and consultancy service focused on identifying the best route, just as happens in ocean racing.

This means that the ship went looking for the conditions most likely to make it faster, which meant it could do without its engine and save up to double the fuel. It’s a navigational philosophy very close to sailing”.

So OceanWings is economically feasible…

“The system works once you can tell the owner that they will break even on their OceanWings investment in five years. We ask for the characteristics of the ship, the route and the frequency of its voyages.

We do a simulation using past weather readings and then we can predict the savings. For instance, if a ship is following the routes from France to North Africa, it will save up to 40% of its fuel. But that figure can be even higher on longer distances”.

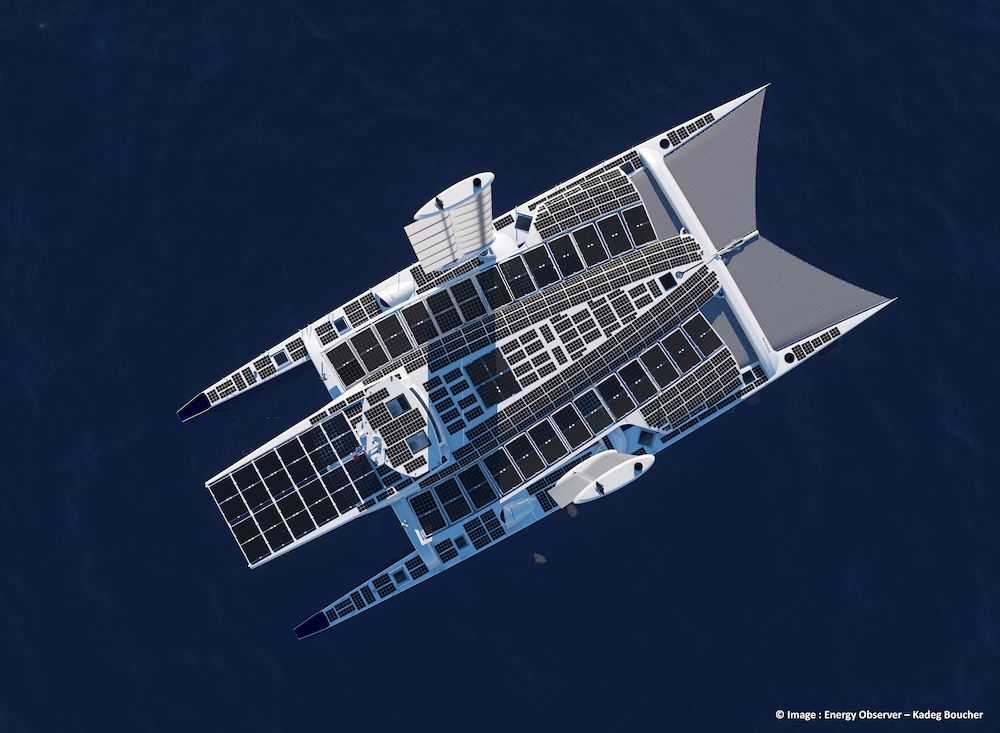

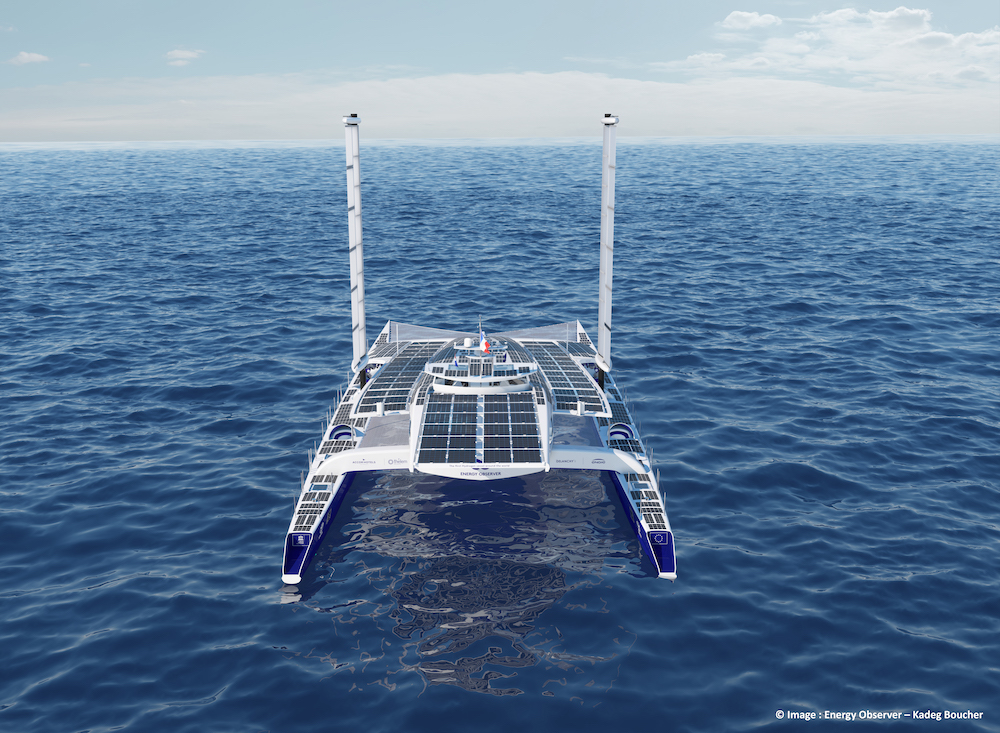

OceanWings, which was installed on Energy Observer, the hydrogen-engined catamaran that sailed around the world, is also aboard your S-Jet foiling cat project in partnership with Airbus. So is it the future?

“It will take more time for sailing. Right now, automatic control of the foils still isn’t possible. You need manual control on a sailing boat.

It will take time. But on motor-powered vessels, by which I mean passenger ships, it is the future. Even though OceanWings is high performance and reliable but there is still a long way to go. But it also proves how much sailing has changed on a technological level”.

And speaking of wingsails and foils, one last question to you as an America’s Cup winner, what do you think of the next one?

“I’m not wild about it. I think it is a pity they abandoned the multihulls. We had found something that allowed different countries to take part with the possibility of developing interesting technologies using accessible budgets. Now they have started with this reactionary solution. I don’t like it though.

At the end of the day, because they involve so many people, skills and money, these boats will have to be interesting. To look at at least. But I don’t know if they will add anything new. I love competition and technology but not when they become inaccessible”.